Is genetic “fitness” predictable?

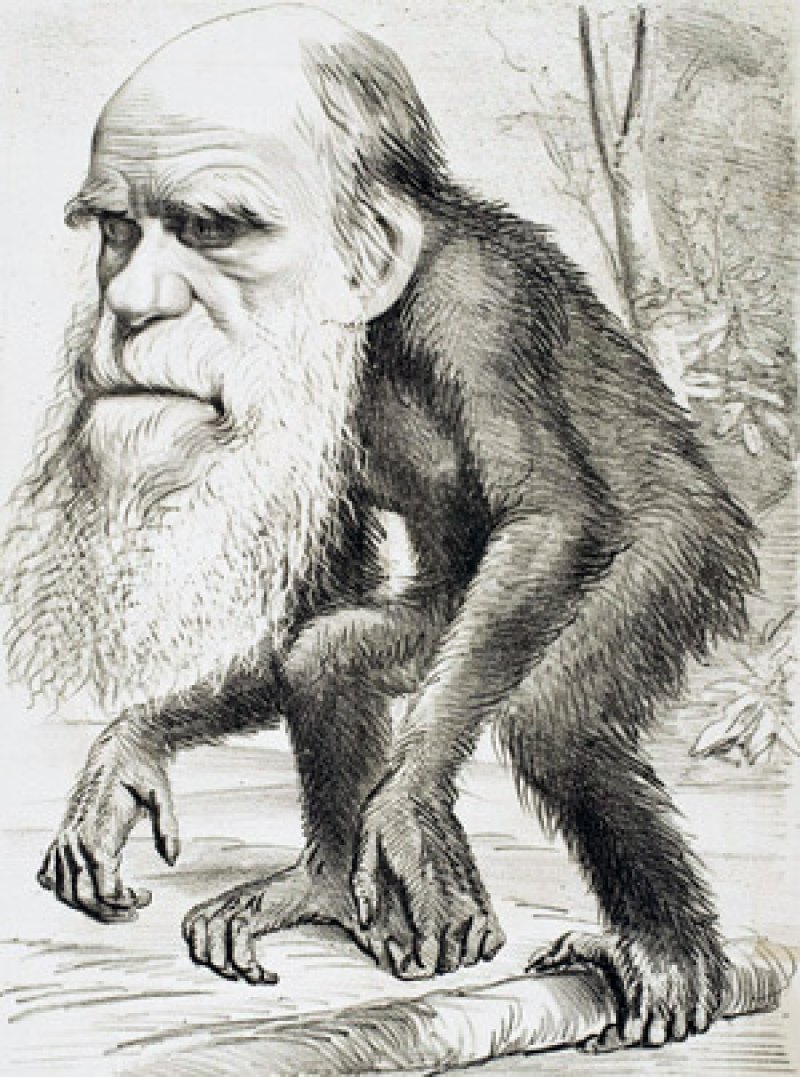

An intriguing experiment finds that it is. Evolution has numerous mechanisms. Descent with modification was the term Darwin used for genetic differences passed on to the next generation. We also know that mutation happens, along with genetic drift, migration and even coevolution due to other species. Mathematicians have long debated the random walk hypothesis–how to predict where a drunken person will end up if they just wander around at random. Evolution has its own random walks, due to things like mutation and genetic drift.

If we were to start evolution over, we would be wildly different due to random walks early on, according to historical contingency and the big impact of early events.

Or would we?

A recent paper in Science detailed an experiment in which a team tried to find out, using hundreds of distinct environments. Twice per day, the least fit (slowest growing) Saccharomyces cerevisiae (called baker’s yeasts, but the same species as in wine and beer) in each unique bio-world would go extinct. The fittest survived. Because the ‘worlds’ were all distinct, and therefore all randomly walking through evolution with their own genetic drift and mutations, historical contingency says they should all have arrived at different evolutionary endpoints in a random fashion, just like the random historical contingency of dinosaurs going extinct allowed us to flourish but we might not if a giant asteroid hit us again.

Yet those random evolutionary endpoints didn’t happen. Evolution instead was downright predictable and in 640 worlds all those lines of yeast came out a lot alike. They defied the random walk of nature. Emily Singer describes it in Quanta magazine,

It’s as if 100 New York City taxis agreed to take separate highways in a race to the Pacific Ocean, and 50 hours later they all converged at the Santa Monica pier.

Instead of being a truly random walk, the study found that survival of the fittest led to diminishing returns for beneficial mutations. An easy metaphor using exercise is the benefit of a walk around the block. An obese person who goes on a walk is going to get a lot of effect while a marathon runner would barely notice. Fitness evolution is more predictable than otherwise assumed, it shows, because evolution is a lot more complex than traditional gene-centric thinking allowed.

What does this mean in the increasingly rancorous debate over GMOs? It may seem a little silly for critics of the technology to believe a precisely-controlled protein that is fine in one plant and can’t possibly express itself in humans can lead to a FrankenCabbage-Scorpion Chimera in another plant, but people writing about science for advocacy groups are stuck with surface-level knowledge of genetics and the environment.

In reality, for a GMO to ruin a plant would take a lot more than a genetic modification.

Hank Campbell is founder of Science 2.0 and an award-winning science writer who has appeared in numerous publications, from Wired to the Wall Street Journal. In 2012 he was co-author of the bestselling book Science Left Behind. Follow him on Twitter @HankCampbell.