Greenpeace was formed between 1969-1972 in Canada initially as a nuclear war protest movement and made famous by their anti-whaling industry campaigns. It has an estimated 2.8 million members worldwide and offices in 45 countries, and a budget of more than US$300 million. Greenpeace International located its headquarters in the Netherlands following the 1998 revocation by Canada Revenue[1] of its charitable status.[2]

Greenpeace has been given non-profit status in a number of countries, including the United States, but both Canada and New Zealand have revoked the organization’s non-profit status, noting that the group’s overly politicized agenda no longer has any “public benefit.” In December 2014, some of its activists faced criminal charges in Peru for desecrating a sacred Incan site with political messages during the UN climate talks in Lima. In 2018 New Zealand’s government again ruled that Greenpeace was “too political” to merit charitable status in that country[3] Germany issued similar findings.[4]) In 2012, Australia’s federal treasurer similarly questioned the organizations legitimacy as a non-profit, charitable, tax-exempt organization.[5] Some reports claim Greenpeace’s combined international campaign expenditures exceed 1 billion Euros.[6])

Greenpeace campaigns include supporting wind and solar energy, and opposing the nuclear, logging and fishing industries. It has long targeted the plastics industry for its use of chemicals. It opposes the use of numerous chemical substances including elemental chlorine. It has been an aggressive campaigner against the consumer electronics industry. In 2006, Greenpeace released its “Guide to Greener Electronics,” condemning the entire industry, saying that no company was doing enough to keep toxic chemicals out of consumer electronics.

A sizable share of its budget in recent years, particularly in North America and Europe, has gone to create campaigns to block agricultural biotechnology products. Greenpeace campaign director Charles Margulis is credited with coining the term “FrankenFood.” In 2001, Lord Melchett, then director of Greenpeace UK, criticized genetically modified crops, telling the House of Lords:

It is a permanent and definite and complete opposition based on a view that there will always be major uncertainties. It is the nature of the technology, indeed it is the nature of science, that there will not be any absolute proof.

In 2021. after the World Health Organization published the results of its global study of the origins of COVID-19, Greenpeace began amplifying the report as ‘proof’ of a “clear link” between biodiversity loss and zoonoses, blaming conventional agriculture. This could foreshadow other activist groups using these findings as support for their attack on the tools of conventional agriculture.

History

In many ways, Greenpeace can be viewed as an extension of the 1960s’ peace and hippy movement. It emerged in Vancouver in 1969 as the “Don’t Make a Wave Committee,” and consisted of a group of Canadian and American expatriate (many of whom were living in self-imposed exile to dodge the Vietnam draft) political activists and hippies.

Its initial motivation was to “bear witness” to U.S. underground nuclear testing at Amchitka, an island off the west coast of Alaska. Its motivations were a mix of environmental concerns about the fate of the island’s sea otters and bald eagles, and a deep-seated aversion to nuclear weapons. This fledgling organization grew from a minor Canadian pressure group to the world’s biggest environmental organization, beginning in 1972. Greenpeace put out an appeal for sympathetic yacht rs to help them protest against French atmospheric nuclear tests in the Pacific. Over the next twenty-five years, this would be Greenpeace’s most ardently fought and famous campaign.

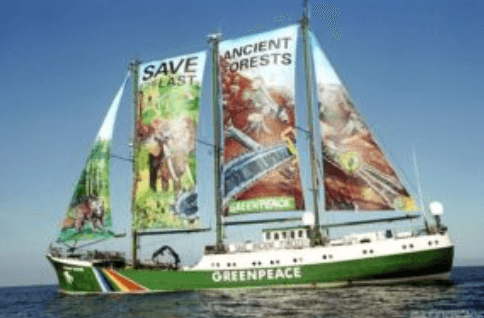

Its most famous protests have been seaborne: intercepting whaling missions or disrupting nuclear tests. It states in its 1983 pamphlet, the Greenpeace Philosophy: “Ecology teaches us that humankind is not the center of life on the planet.” Its tactics have been confrontational, eschewing compromise. That’s evoked condemnation but also praise and admiration by activists. Paul Clarke, an anti-GMO campaigner with Greenpeace, wrote: “The way the organization dealt with issues such as nuclear testing and commercial whaling seemed unsettlingly non-conformist—even revolutionary—when compared with the activities of the more established conservation organizations, such as the Sierra Club and the Audobon Society. … [A]s the mainstream groups, corporations, and governments quickly learned, the use of high-profile actions and demonstrations coupled with taking international environmental issues to the streets seemed to produce results

Throughout its history, the advocacy environmental group has been criticized by a number of groups, including national governments, members of industry, former Greenpeace members, scientists, political groups, and other environmentalists. Early Greenpeace founding member, ecologist Dr. Patrick Moore, who served for nine years as head of Greenpeace Canada, is a sharp critic of the organization. He left the organization in 1986: As he wrote in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece,

The breaking point was a Greenpeace decision to support a world-wide ban on chlorine. Science shows that adding chlorine to drinking water was the biggest advance in the history of public health, virtually eradicating water-borne diseases such as cholera. … We all have a responsibility to be environmental stewards. But that stewardship requires that science, not political agendas, drive our public policy.

According to Wyn Grant, a British professor of politics at the University of Warwick who his written extensively on pressure groups, characterized Greenpeace as a hierarchical and undemocratic organization which allows very little control of its members over the campaigns the organization embarks upon. Echoing similar criticisms from numerous other political scientists, he said it has a strictly bureaucratic and borderline authoritarian internal structure; a small group of individuals have control over the organization in both international and local levels; local action groups are totally dependent on the central body; and the rank and file are excluded from most decisions.

An article in Forbes in 1991 entitled “The Not So Peaceful World of Greenpeace,” criticized the organization’s lack of accountability, accusing it of cleverly manipulating the world’s media. “Outfits like Greenpeace attack big business as being faceless and responsible to no one,” the authors argued. “In fact, that description better fits Greenpeace than it does modern corporations that are regulated, patrolled and heavily taxed by governments, reported on by an adversarial press and carefully watched by their own shareholders. There’s little accountability for outfits like Greenpeace.”

Organization

Greenpeace is a confederation of multiple individual country and regional organizations with varying charters and public reporting requirements based on their locations.

Greenpeace USA

* Greenpeace Fund, Inc., Also Known As: Greenpeace

- Physical Address: 702 H Street NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20001

- EIN: 95-3313195

- Web URL: www.greenpeacefund.org; Blog URL: greenpeaceblogs.org/

- Telephone: (800) 326-0959; Facsimile: (202) 319-1553

- Contact: Supporter Care [email protected]

- NTEE Category: C Environmental Quality Protection, Beautification, C34 Land Resources Conservation, C Environmental Quality Protection, Beautification, C32 Water Resource, Wetlands Conservation and Management, C Environmental Quality Protection, Beautification, C20 Pollution Abatement and Control Services

- Ruling Year: 1979

- 2011 revenue $12.9 million/ expenses $14.6 million

- Listed board members/key staff: Robert Fox, COO

* Greenpeace, Inc. (USA)

- Physical Address: 702 H Street NW, Ste 300, Washington, DC 20001

- EIN: 52-1541501

- Web URL:www.greenpeaceusa.org; Blog URL: greenpeaceblogs.org/

- Telephone: (800) 326-0959; Facsimile: (202) 462-4507

- Contact: Supporter Care, [email protected]

- NTEE Category: C Environmental Quality Protection, Beautification; C34 Land Resources Conservation; C Environmental Quality Protection, Beautification; C32 Water Resource, Wetlands Conservation and Management; C Environmental Quality Protection, Beautification; C20 Pollution Abatement and Control Services

- Ruling Year: 1988

- 2011 revenue $33.8 million/ expenses $32.4 million

- Listed board members/leadership: Phil Radford

* Greenpeace Foundation

- Physical Address: 1118 Maunawili Rd, Kailua, HI 96734

- EIN: 99-0175939

- Web URL:www.greenpeacefoundation.org

- Telephone: (808) 236-4388

- NTEE Category:T Philanthropy, Voluntarism, and Grantmaking; T20 (Private Grantmaking Foundations);

- Ruling Year: 1978

- 2011 (last year reported) revenues $17,000/ expenditures $6,000

- Listed board members: Sue White, Don White, Jessica Malcom

Other Regional Greenpeace NGOs (NOTE: Greenpeace organizations exist in every European and Asian country, and in many countries around the world)

- Greenpeace Mexico

- Greenpeace UK

- Greenpeace Aotearoa New Zealand

- Greenpeace Australia Pacific

- Greenpeace Chile

- Greenpeace East Asia

- Greenpeace India

- Greenpeace Nordic

- Greenteams

CAMPAIGNS / ACTIVITIES

GMOS

Greenpeace has a consumers’ shopping guide to avoiding GMOs. It supports a national movement to require labels and other disclosures wherever GMOs are present in the food supply as a tactic to get GMOs banned. It engages an international behemoth of a grassroots mailing list wherever and whenever regulatory decisions loom regarding testing or market approval of food crops containing novel genes. In past years, Greenpeace has housed a dedicated anti-biotechnology campaign staff in the U.S., at their International Headquarters and via various other country entities. They are currently most active on anti-GMO campaigns in South Asia.

Greenpeace was an early and active opponent of genetically engineered crops. In 2001, Lord Melchett, then director of Greenpeace UK (and later head of the UK organic farming trade group, The Soil Association, condemned the then emerging technology in an appearance in front of the House of Lords:

It is a permanent and definite and complete opposition based on a view that there will always be major uncertainties. It is the nature of the technology, indeed it is the nature of science, that there will not be any absolute proof.

In September 2013, several prominent scientists published a letter condemning Greenpeace and other NGOs for its opposition to Golden Rice, which is genetically engineered to produce beta carotene, a precursor to Vitamin A, as a means to fight vitamin deficiency in developing countries. The World Health Organization estimates that, around the world, 190 million children under the age of five may have a vitamin A deficiency. Of those, some 250,000 to 500,000 suffer blindness. By recent estimates, providing children and families easy access to vitamin A could save 600,000 lives a year in Africa, Asia, and other developing countries. In their letter, the scientists state, “If ever there was a clear-cut cause for outrage, it is the concerted campaign by Greenpeace and other nongovernmental organizations, as well as by individuals, against Golden Rice.”

In 2016, 107 Nobel laureates sharply criticized the organization in a letter urging it to end its opposition to GMOS and Golden Rice. The letter stated:

We urge Greenpeace and its supporters to re-examine the experience of farmers and consumers worldwide with crops and foods improved through biotechnology, recognize the findings of authoritative scientific bodies and regulatory agencies, and abandon their campaign against “GMOs” in general and Golden Rice in particular. Scientific and regulatory agencies around the world have repeatedly and consistently found crops and foods improved through biotechnology to be as safe as, if not safer than those derived from any other method of production. There has never been a single confirmed case of a negative health outcome for humans or animals from their consumption. Their environmental impacts have been shown repeatedly to be less damaging to the environment, and a boon to global biodiversity.

Greenpeace Southeast Asia was the main agent blocking the introduction of GMO virus-resistant papaya into Thailand. The saga is detailed by Sarah Davidson in a journal article ‘Forbidden Fruit: Transgenic Papaya in Thailand’.[7] Greenpeace Southeast Asia in February 2011 destroyed a trial site of Bt talong (eggplant) at the University of Los Banos in the Philippines[8], although according to ISAAA the plants which were destroyed were the non-transgenic controls.[9]

Greenpeace Southeast Asia was the main agent blocking the introduction of GMO virus-resistant papaya into Thailand. The saga is detailed by Sarah Davidson in a journal article ‘Forbidden Fruit: Transgenic Papaya in Thailand’.[7] Greenpeace Southeast Asia in February 2011 destroyed a trial site of Bt talong (eggplant) at the University of Los Banos in the Philippines[8], although according to ISAAA the plants which were destroyed were the non-transgenic controls.[9]

Greenpeace has campaigned consistently against Golden Rice in the Philippines. The website declares: “GE ‘Golden’ rice does not address the underlying causes of VAD, which are mainly poverty and lack of access to a healthy and varied diet. This GE rice is a technological fix that may generate new problems.”[10] Greenpeace scored a major success against Golden Rice in China when it led a press scandal accusing researchers of using Chinese children as ‘guinea pigs’ in a vitamin A trial.[11]

India banned foreign funding of local campaigns after its intelligence agency warned that Greenpeace’s activism was a threat to the local economy. Greenpeace has ties to Vandana Shiva and her organization Navdanya. Shiva has been a consultant to Greenpeace Australia. Shiva has blamed the high cost of GM cotton seeds for the suicides of indebted Indian farmers. Her campaign along with other groups included Greenpeace’s plans to protest genetically modified soy and corn with “crop circles.”

KEY PEOPLE

Greenpeace International

- Senior Scientist Janet Cotter

- North American (Canadian-based) GMO Campaign lead Eric Darier

Greenpeace USA: (reports $13 million in salaries)

- Robert Fox, COO (also Greenpeace Fund), ($100,000)

- Karen Topakian, chair Greenpeace USA

- Tom Newmark

- Antha Williams

- David Hunter

- Sharyle Patton

- Valerie Denney

- Daniel Rudie

- Jigar Shah

- Bryony Schwan

- Liz Gilchrist

- David Pellow

- Daniel J. McGregor, director of development ($155,000)

- Philip D. Radford, executive director ($166,000)

- Thomas W. Wetterer, general counsel & COO, ($130,000)

- Thomas S. Camerlink, CIO ($120,000)

- Nathan Santry, director of actions, ($120,000)

- Kevin Grandia, new media director, ($140,000)

- Davide Barre, director of online communications, ($110,000)

Greenpeace Fund (USA): (reports $867,000 in salaries – and grants of $5.6 million to Greenpeace Europe in 2011 and $4 million to Greenpeace USA campaigns)

- David Chatfield, chair

- Jeffery Hollender

- Ellen McPeake

- Liz Gilchrist

(see also Greenpeace USA)

- Robert Fox, COO (see also Greenpeace USA) ($100,000)

- Philip D. Radford, executive director (see also Greenpeace USA) ($166,000)

- Thomas W. Wetterer, general counsel deputy COO, ($120,000)

Greenpeace Asia:

- Daniel Ocampo, Sustainable Agriculture Campaigner, Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

FUNDING SOURCES

Greenpeace claims to receive no corporate, political or government funding; however, one of their large sources of income is reportedly a percentage of the Dutch Lottery, they have received direct financial support from the EU, benefit from various Green Party political sources in Europe, and received donations from corporate philanthropic arms and sales percentage allocations from “socially responsible” businesses, like Ben & Jerry’s, whose competitors’ products Greenpeace campaigns attack. Greenpeace Brazil also derived income from the sales of their own line of organic products.

In addition to the above noted sources, Greenpeace derives its income from large foundations and individual donors. Their 2008 International office budget was reported to be in excess of 200 million Euros.

While claiming no political influence, Greenpeace has lost their charitable tax exempt status in numerous countries (including Germany, Canada and Australia) for engaging in non-charitable political activities. Their 2006 German budget alone was reported at 40 milion Euros.[6]

AFFILIATIONS

- Veejay Villafranca, Philippine-based, award winning photo journalists collaborates regionally with Greenpeace Philippines and Greenpeace Asia an[13] and helps develop anti-GMO multimedia content for their campaigns.[14]

CRITICISMS

Patrick Moore served as Greenpeace International executive director and was one of the organization’s founding members. He publicly disavowed the organization in 1986 noting, “the environmental movement is not always guided by science” and that the organization had been co-opted by “political activists or environmental entrepreneurs” who had abandoned “scientific objectivity in favor of political agendas.”

Moore states, “Greenpeace has evolved into an organization of extremism and politically motivated agendas” who run campaigns based on “fear to implement their political agendas.”[15] Moore told Wired Magazine that the term sustainable development is “oxymoronic” to Greenpeace, which along with many in the environmental movement he claims have “dangerous” to society with their “anti-science agenda.”[16]

Greenpeace has come in for strong criticism for its stance on Golden Rice by Patrick Moore, a former Greenpeace founding member and executive director, who fronted an ‘Allow Golden Rice’ campaign targeting Greenpeace offices with banners and media stunts in Europe.[17] There was extensive and positive press coverage of the criticisms against Greenpeace who Moore claims is committing crimes against humanity.[18]

A 2011 Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) report cited Greenpeace as part of a “a growing radicalized environmentalist faction within Canadian society” adding, “Criminal activity by Greenpeace activists typically consists of trespassing, mischief, and vandalism, and often requires a law enforcement response.” Referring the Greenpeace activities, the RCMP report stated, “Tactics employed by activist groups are intended to intimidate and have the potential to escalate to violence.”[19]

The New Zealand Department of International Affairs and Charities Registrations denied Greenpeace’s application for charitable status citing both political (non-charitable) and illegal activities, noting, “Greenpeace was involved in illegal activities, such as trespassing; therefore it was not maintained exclusively for charitable purposes as illegal purposes are not charitable.” [20]

Indonesian lawmakers have accused Greenpeace of illegal activities with the support of foreign donors. “There are reasons to believe that many international NGOs like Greenpeace have been running illegal economic investigations in Indonesia besides their formal missions,” said Desmond Junaidi Mahesa of the Greater Indonesia Movement Party, referring to the organizations’ funding, which mostly comes from foreign donors.[21]

In October 2013 the UK environment secretary Owen Paterson made international headlines when he said that opposition to Golden Rice was “wicked”.[22]

A French journalist under the pen name Olivier Vermont wrote in his book La Face cachée de Greenpeace (“The Hidden Face of Greenpeace”) that he had joined Greenpeace France and had worked there as a secretary. According to Vermont he found misconduct, and continued to find it, from Amsterdam to the International office. Vermont said he found classified documents according to which half of the organization’s €180 million revenue was used for the organization’s salaries and structure. He also accused Greenpeace of having unofficial agreements with polluting companies where the companies paid Greenpeace to keep them from attacking the company’s image.[23] Animal protection magazine Animal People reported in March 1997 that Greenpeace France and Greenpeace International had sued Olivier Vermont and his publisher Albin Michel for issuing “defamatory statements, untruths, distortions of the facts and absurd allegations”.

Writing in Cosmos (magazine), journalist Wilson da Silva reacted to Greenpeace’s destruction of a genetically modified wheat crop in Ginninderra as another sign that the organization has “lost its way” and had degenerated into a “sad, dogmatic, reactionary phalanx of anti-science zealots who care not for evidence, but for publicity”.[24]

See Also

Resources

References

- 1 http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/

- 2 http://www.iea.org.uk/publications/research/canada-leaves-greenpeace-red-faced

- 3 http://business.scoop.co.nz/2011/05/09/greenpeace-too-political-to-register-as-charity-nz-court/

- 4 http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/2843#.UlLDdVCsidk

- 5 http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/latest-news/treasurer-wayne-swan-questions-greenpeace-tax-free-status/story-fn3dxity-1226292364086

- 6 http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/2843#.U1EyCvldWSo

- 7 http://www.plantphysiol.org/content/147/2/487

- 8 http://www.bic.searca.org/press_releases/20111/jun03.html

- 9 http://www.isaaa.org/kc/cropbiotechupdate/article/default.asp?ID=7391

- 10 http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/campaigns/agriculture/problem/genetic-engineering/Greenpeace-and-Golden-Rice/

- 11 http://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/news/blog/24-children-used-as-guinea-pigs-in-geneticall/blog/41956/

- 12 http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/2843#.U1EyCvldWSo

- 13 http://geromesoriano.blogspot.com/2013/06/veejay-villafranca-working-in.html

- 14 http://www.greenpeace.org/seasia/ph/multimedia/slideshows/greenpeace-2012/Anti-GMO-March-in-the-Philippines1/

- 15 http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB120882720657033391

- 16 http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/12.03/moore.html?pg=2&topic=&topic_set=

- 17 http://www.allowgoldenricenow.org/

- 18 http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/former-greenpeace-leading-light-condemns-them-for-opposing-gm-golden-rice-crop-that-could-save-two-million-children-from-starvation-per-year-9097170.html

- 19 http://news.nationalpost.com/2012/07/29/greenpeace-denies-growing-more-radical-there-is-a-difference-between-breaking-the-law-and-criminal-activities/

- 20 http://www.nbr.co.nz/article/court-questions-political-and-illegal-activity-greenpeace-charity-bid-bc

- 21 http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2011/10/26/lawmakers-accuse-greenpeace-illegal-activities.html

- 22 http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/oct/14/gm-crops-is-opposition-to-golden-rice-wicked

- 23 Développement durable : le concept dévoyé qui ne doit plus durer !, from the Author of “La Servitude Climatique”.

- 24 “The sad, sad demise of Greenpeace”. Cosmos (magazine). July 14, 2011″>Wilson da Silva. “The sad, sad demise of Greenpeace”. Cosmos (magazine). July 14, 2011