Driving straight through from New York City to San Francisco is possible, but a more leisurely journey, with stops at particular points of interest, is certainly more informative. So it is with genetic testing to glimpse the genotypes of the offspring possible from two individuals. GenePeeks is a “genetic information company” that offers a deep-dive into 1000+ key genes that can tell potential parents more than can sweeping views of entire genomes.

Parents selecting junior’s traits may conjure images of the 1997 film Gattaca when a couple gazing at an ancient computer screen orders up a brother for their son. GenePeeks’ test collection, however, is perhaps most useful to catalog genetic profiles of egg and sperm bank donations, enabling couples to essentially swipe one way to accept, or the other way to decline, a gamete — a little like the dating app Tinder, based on whether recessive mutations are in the same genes as in the fertile partner. If they are, a possible child has a 25% risk of inheriting the associated disease, according to Mendel’s first law.

The GenePeeks screen must be ordered by a health care provider and is regulated under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), not FDA.

“Is your child still alive?”

The compelling need for panels of gene tests that cover not only rare diseases, but rare variants of rare diseases, is what led CEO Anne Morriss to found the company. Days after coming home from the hospital after giving birth to her son Alec in 2006, she got a call asking a chilling question: “Is your child still alive?”

He was, but newborn screening from his heelprick blood test had detected medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCAD). Already, lack of an enzyme was impairing the baby’s ability to metabolize certain fatty acids into glucose. The sleepy baby would soon become frighteningly lethargic as his cells ran out of energy. Over time, the unchecked biochemical derangement would have damaged his brain and liver. Fortunately, diet makes a huge difference – but new parents need to know that it’s necessary, and ASAP.

“It was scary in the beginning because historically, before the disease was discovered, clinicians believed it was a major cause of SIDS because there’s no external evidence. You have to keep the blood sugar up around the clock, feeding every few hours. If we had gotten the info that Alec was at risk we would have changed the protocol the minute he was born, making sure he eats sugar water. The outcome can be catastrophic if you don’t intervene. I feel very lucky in retrospect,” Morriss said.

MCAD deficiency (spoiler alert!) is at the heart of Jodi Picoult’s 2016 novel and soon-to-be film Small Great Things. The condition is autosomal recessive: Both parents are carriers. It affects one in 17,000 newborns in the U.S. each year. Anne had used a sperm donor who obviously (in retrospect) hadn’t been screened for carrier status – nor had she.

Morriss, who has an MBA from Harvard and lived near Boston’s biotech epicenter, Kendall Square, quickly became aware of the “big gap from what scientists were figuring out and the standard of care in clinical practice.” When a friend introduced her to Lee Silver, professor emeritus of molecular biology at Princeton, a collaboration was born that led quickly to the conception and gestation of GenePeeks. “He invented a novel and exciting way to look ahead and predict what would happen when two people conceived in a way to give more visibility into the risks,” she recalled.

Morriss, who has an MBA from Harvard and lived near Boston’s biotech epicenter, Kendall Square, quickly became aware of the “big gap from what scientists were figuring out and the standard of care in clinical practice.” When a friend introduced her to Lee Silver, professor emeritus of molecular biology at Princeton, a collaboration was born that led quickly to the conception and gestation of GenePeeks. “He invented a novel and exciting way to look ahead and predict what would happen when two people conceived in a way to give more visibility into the risks,” she recalled.

Silver’s 1997 book Remaking Eden pretty much laid down the basic idea. An article in Science announced the imminent arrival of GenePeeks in October 2012.

Building a better carrier test

Back in the 1970s, when carrier screenings began, economics tended to drive the selection of diseases and who to test. And so Tay-Sachs disease carrier screens were promoted to people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and for sickle cell disease carriers to those of African descent.

Those first tests were protein-based, and so the question of the differing dangers of various mutations didn’t arise – Tay-Sachs carriers had half the normal amount of the implicated enzyme, and sickle cell carriers had half of their hemoglobin molecules migrate differently in an electrical field. These tests of phenotype were actually more accurate, and even today newborn screening genetic tests are backed up with biochemical assays to tell whether genotype actually translates into phenotype. Sometimes it doesn’t, resulting in anxious parents awaiting a genetic guillotine.

For many recessive diseases, the first tests to be offered commercially probed the most common variant. Tests expanded with more research. Cystic fibrosis provides a telling example. About 73 percent of people with CF worldwide have at least one copy of the mutation F508 (formerly known as delta F508 but many people didn’t have triangles on their keyboards. The “F” refers to the amino acid phenylalanine, the genetic instructions for which are missing from position 508 in the gene.) Prevalence varies. F508 is in 90 percent of CF patients in the UK, yet only 48 percent of those in Brazil, for example.

Other variations on the CFTR theme were soon discovered, and over the years, CF carrier tests expanded, from 20 or so mutations, to 90, to more than 100. 2,000+ variants are now known. Two other common variants are G551D, present in 3 percent of CF patients worldwide, and R117H, in 2 percent of patients. Another, with the catchy name 3659delC, affects 5 percent of patients in Sweden, but only 0.7 percent in the US and 0.2 percent in Canada. Considering ancestry is important in choosing genetic tests!

Claim 3 of Silver’s patent #8,620,594 spells out exactly what’s checked: “single base substitutions, insertion/deletions, copy number polymorphisms and combinations thereof at defined genetic loci in genomic DNA samples obtained from said first and second potential parents.”

In English: one type of DNA base (A, C, T, or G) replacing another; stretches of bases added or removed; short base sequences repeated a differing number of times among individuals, and all combinations of ways the tested genes can vary between the parents of a hypothetical child. It’s not genome or exome sequencing, or analysis of chromosomes and gene-gene interactions.

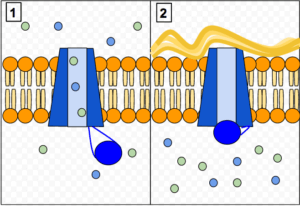

The algorithm models meiosis, when egg and sperm form as their chromosome sets are pulled into separate cells and the egg bolstered and sperm whittled down. But it does much more. The invention also teases out subtle characteristics of gene variants, such as population frequencies and evolutionary conservation, a measure of a protein’s importance. Of direct clinical significance is whether a person’s two variants of a gene lie near each other on the same chromosome or are one on each copy. Knowing such “cis” and “trans” positioning (terms used in genetics long before in gender identity) is crucial because neighboring genes would likely wind up in the same sperm or egg, but if on separate chromosomes, not.

The algorithm models meiosis, when egg and sperm form as their chromosome sets are pulled into separate cells and the egg bolstered and sperm whittled down. But it does much more. The invention also teases out subtle characteristics of gene variants, such as population frequencies and evolutionary conservation, a measure of a protein’s importance. Of direct clinical significance is whether a person’s two variants of a gene lie near each other on the same chromosome or are one on each copy. Knowing such “cis” and “trans” positioning (terms used in genetics long before in gender identity) is crucial because neighboring genes would likely wind up in the same sperm or egg, but if on separate chromosomes, not.

Beyond ‘benign’ or ‘pathogenic’

The GenePeeks preconception screen doesn’t just detect mutations. It also predicts their effects on the encoded proteins, which in turn affects health. In cystic fibrosis, different mutations alter CFTR protein in different ways, some more devastating than others. The common F508 mires the protein in the cells’ innards, keeping it from reaching the cell membrane and functioning as an ion channel. Trapping salts in the cells dries out secretions. F508 abolishes protein activity and so people with one or two copies have severe disease. For the rarer R117H mutation, the ion channels reach the cell surface, but once there most don’t open sufficiently. People with two copies of this mutation would have a later onset of symptoms than those with one or two F508s, and patients who have F508 and R117H lie in between.

Sometimes gene variants complement, so that both parents are carriers but the combination isn’t harmful. If a gene variant from the egg affects one part of the encoded protein and the one in the sperm affects another part, and neither is essential to the protein’s function, then tests that don’t go farther than mutation identification might predict a 25 percent chance of a sick child when there’s no elevated risk.

Lee Silver calls the evaluation part of their technology a “gene dysfunction tool” that scores variants based on damage. The approach is much more illuminating than the common strategy of declaring a gene variant, in isolation, “benign” or “pathogenic.” “What we do is a huge difference from what the rest of the community is doing, coming in at the disease level.”

Another limitation of gene variant databases such as ClinVar is the confusing “variants of uncertain significance” (VUS) that tell a patient little more than that yes, your gene variant isn’t the “normal” one, but no, it hasn’t been associated with symptoms. Yet. VUS are often of unknown impact because not enough cases have been reported to statistically establish a mutation-disease connection. And that’s where GenePeeks’s deeper dive comes in. “We don’t wait for a variant to show up in a patient, but validate our analysis on a gene-by-gene basis” considering the effect on the protein, Silver said.

Choosing eggs

A couple without fertility concerns might use carrier test panels (several other companies offer tests too) to deduce which recessive diseases their offspring might inherit, revealing what to check using standard prenatal diagnostic techniques. (I wrote about new recommendations for expanded carrier screening at the Genetic Literacy Project recently.)

Preconception carrier screening is especially helpful in the type of situation that Morriss faced. Stephanie Frickleton, donor program director at Pacific NW Fertility, has helped more than 1,500 donor egg recipients.

The donor and the male partner provide saliva for the carrier testing. If they have mutations in the same gene, then the risk to offspring of inheriting both mutations is 25 percent, modified with the gene dysfunction tool.

Frickleton describes one couple. “They had a fail with their first choice of egg donor and then the second choice had the same mutation as the husband, so we tested a third donor and she didn’t, so they created embryos in vitro and had the transfer. At first the patients were disappointed because they‘d connected to the donors, but they were happy and relieved that they dodged a bullet.”

I think GenePeeks provides much more than a peek! It is a carefully curated glimpse into a future person’s health. Maybe the Gattaca scenario isn’t so futuristic after all.

Ricki Lewis is a long-time science writer with a PhD in genetics. She writes the DNA Science blog at PLOS and contributes regularly to Rare Disease Report and Medscape Medical News. Ricki is the author of the textbook Human Genetics: Concepts and Applications (McGraw-Hill, 12th edition out late summer); The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It (St. Martin’s Press, 2013) and the just-published second edition of Human Genetics: The Basics (Routledge Press, 2017). She teaches Genethics online for the Alden March Bioethics Institute at Albany Medical College and is a genetic counselor at CareNet Medical Group in Schenectady, NY. You can find her at her website or on Twitter at @rickilewis

For more background on the Genetic Literacy Project, read GLP on Wikipedia.