The Sierra Club, founded by John Muir in 1892 to support wilderness outings and conservation in the American west, is now on a different campaign: scaring the bejeebies out of people to raise money. The once venerable organization, once known for its eco-pragmatism, is twisting the science about bees and pesticides. Literally hundreds of thousands of people who have supported one green organization or event in recent years opened their mailboxes in the past few months to find a scare letter of epic proportions written by Sierra’s executive director Michael Brune:

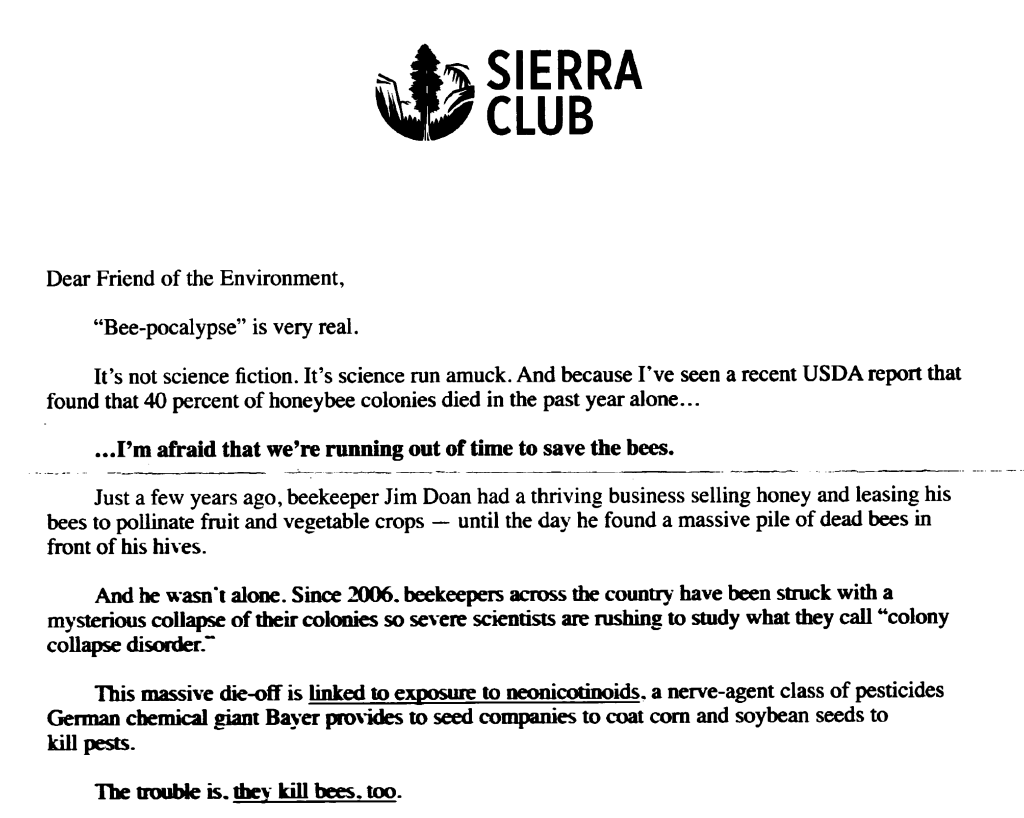

More than two years ago, the Sierra Club embarked on a campaign to convince the public that neonicotinoids–a class of systemic pesticide popular in the US, Australia, Europe and elsewhere that  helps fight pests threatening corn, soy, cotton and canola farmers–are decimating the US honeybee population. Its website is filled with articles claiming a worldwide die-off of bees. The campaign has been advocacy group gold: helpless pollinators fighting a losing war against Big Bad Agriculture. The bogeyman for years was Monsanto even though the seed giant does not make neonics. More recently, with Monsanto agreeing to a takeover by the Bayer Corporation, which is one of the manufacturers of neonics, the campaign now targets the German-based chemical and pharmaceutical giant.

helps fight pests threatening corn, soy, cotton and canola farmers–are decimating the US honeybee population. Its website is filled with articles claiming a worldwide die-off of bees. The campaign has been advocacy group gold: helpless pollinators fighting a losing war against Big Bad Agriculture. The bogeyman for years was Monsanto even though the seed giant does not make neonics. More recently, with Monsanto agreeing to a takeover by the Bayer Corporation, which is one of the manufacturers of neonics, the campaign now targets the German-based chemical and pharmaceutical giant.

In a recent series of letters sent out this fall as part of this ongoing multi-year fund-raising effort, Brune makes the case that neonics are behind Colony Collapse Disorder and responsible for a 44 percent decline in bee populations:

Another scare email from the Sierra Club in late September pointed to the insecticide naled, which the advocacy group claimed resulted in a catastrophic loss of bees in South Carolina hives this summer. In this email–also asking for donations and other support–the organization stated:

Millions of bees dead. Victims of acute pesticide poisoning from Naled, meant for controlling mosquitoes. …The only way we can stop giant pesticide companies like Monsanto is by standing together.

If you are worried about pollinators, there might be a reason to hesitate before opening up one’s wallet. Almost none of the information about the naled incident or the ‘bee crisis’ is presented accurately or in context.

Naled misrepresentations

Naled is an insecticide that has been used on mosquitos since 1959, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency. It is not a neonic. It also does not persist in the environment. But as the EPA has warned, acute high exposure can be fatal to bees and other insects. Naled users and beekeepers are advised to work together on timing the application of naled to when bees aren’t foraging, and bee hives are supposed be covered when naled is applied. According to the Washington Post, a Dorchester County, SC, contractor used the pesticide one morning in August in an attempt to kill mosquitoes that might spread the Zika virus. Unfortunately, local bee owners were not informed and the application killed millions of honeybees.

In other words, it was an accident that had nothing to do with the claims of compromised bee health. Moreover, the Sierra Club has refused to throw its weight behind GMO mosquitoes, which could fight the Zika virus with minimal use of potentially dangerous insecticides. In other words, their foot-dragging on this issue almost ensures that catastrophic mishaps like the South Carolina incident that killed so many bees will happen again.

But let’s return to the Sierra Club’s egregious manipulation of the science. Neonicotinoids are extremely effective. Applied to the soil, sprayed on the crop or used as a seed treatment, they eventually reach the pollen and nectar, which is ingested by insects, discouraging pests from wreaking havoc on crops. The seed treatment lowers the amount of pesticides used by 10 to 20 fold, decreasing the need for open spraying of the plant, a genuine sustainability benefit.

Neonics were phased in without incident in the 1990s. But an age-old problem in the bee world—a periodic and unpredictable dramatic rise in bee deaths in one region or another around the world that is tracked in the literature going back multiple centuries—reemerged in the United States in 2004. Bee death rates approached 60 percent in California. Beekeepers called it the vampire mite scare because of its likely link to Varroa mites—parasites that feed on the bodily fluids of bees.

The blaming explanatory narrative began to change in 2006, when new waves of bee deaths were reported around the world. Anti-biotechnology activists at first fingered GMOs. “There are many reasons given to the decline in Bees, but one argument that matters most is the use of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) and “Terminator Seeds” that are presently being endorsed by governments and forcefully utilized as our primary agricultural needs of survival,” argued the anti-globalization group Global Research, in what amounted to a rhetorical and circumstantial argument. There was no evidence, however. As GMOs gained favor with the science community and the link to biotech crops seemed increasingly far-fetched, the focus of activist groups shifted and a new culprit was identified: neonicotinoids.

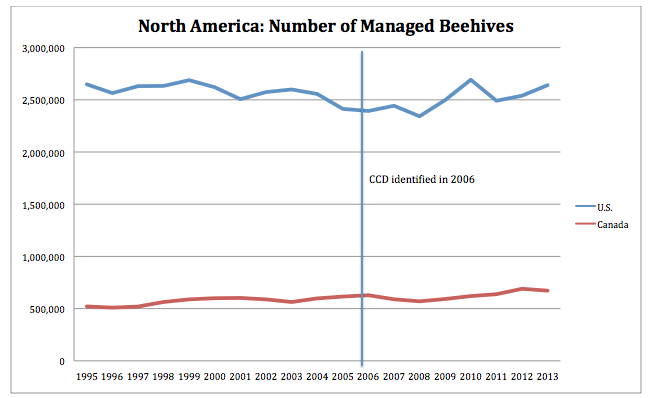

A brief surge in over winter bee deaths in 2011-13 fueled a spate of worldwide headlines about an impending bee-apocalpyse. But a funny thing happened on the way to Armageddon. Bee hive numbers soon recovered substantially from the unique 2006 incident and the multi-winter problems earlier this decade to surge to their highest levels in decades.

Deconstructing Sierra Club’s claims

The 44 percent number is misleading. This figure noting bee losses in 2015-16 sounds scary (nearly half of our bees are gone!), but it conflates two things that commonly happen to bees–winter and summer die-offs–that are quite different in importance. Hives naturally experience losses of bees every winter, often between 10 and 22 percent but sometimes the numbers trend higher. These year-to-year fluctuations are considered normal. But even in bad years, bees usually overcome the drop-off in numbers with their rapid reproduction rates. Second, during the summer, bees may die but they only live for about six weeks. At the same time, bees naturally reproduce and replenish their hives very quickly during the summer. This can more than make up for wintertime losses. So the 44 percent one-year figure is very misleading, as government officials have noted.

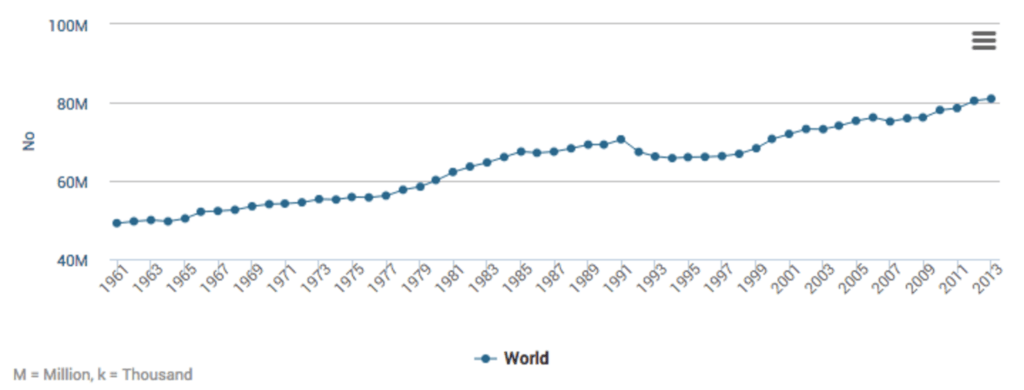

We’re not facing a honeybee crisis. Colony Collapse Disorder was a phenomenon that happened in the mid-2000s and has not reoccurred since, says Dennis Van Engelsdorp, the University of Maryland researcher who coined the term CCD. According to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, the overall population of domestic bees is increasing, reaching highs not seen in decades:

The European Commission enacted a two-year ban on neonics in 2014 even though data at the time of the ban showed no relationship between neonics and disease. Since, studies have shown no effect on bee colony growth during the duration of the ban. EU COLOSS and EPILOBEE group figures show that colony losses were lowest in 2013-2014, before the ban was enacted, and rose to 17.4 percent, during the duration of the ban.

In Australia and in Western Canada, where farmers are heavy users of neonics, bee health is robust. US and Canadian hive numbers have been trending upwards. But that increase is not a straight line. Populations have taken hits–such as around 2006 and during the cold winters earlier this decade–but the overall numbers are not declining.

As the Washington Post’s Wonklbog wrote in 2015, it’s time to “Call off the bee-poclapyse”–you know, the one that the Sierra Club is ranting on about to frighten some loose change our of your pockets.

There is no question that bee health is not what most scientists would say is ideal. But study after independent study–by various government-backed researchers and even by some activist researchers who sometimes seem to be hoping for bad news about bees to further their doomsday narrative about pesticides and modern agriculture–have now shown that neonics and pesticides are not driving bee deaths. Tops on the list are habitat loss; the impact of commercial bee keeping on bee health (transporting bees from farm to farm with little time to acclimate); and Varroa mites and other parasites and diseases.

“Honey beekeepers with five or more colonies reported Varroa mites as the leading stressor affecting colonies,” said the USDA in its latest pollinator health survey, released last May. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released its first of four reports on neonics use earlier this year and concluded there is minimal risk to honey bees from the neonic (imidacloprid) seed treatments for tuber, bulb, brassica (including canola) vegetables and corn.

Could pesticide use, from neonics to organic pesticides, play a role in bee health? Of course; many are designed to kill pests and if misused can contribute to problems. But that’s a far cry from the irresponsible neonic alarm bells set off by the Sierra Club. In fact, studies show that other pesticides, such as pythrethroids and organophosphates, which some ‘environmentalists’ have suggested should be substituted for neonoics (and are now being used in parts of Europe where temporary bans are in place) pose far more significant health hazards to bees–and to humans. According to a recent report in Phys.org–widely respected for its independent science perspective:

Could pesticide use, from neonics to organic pesticides, play a role in bee health? Of course; many are designed to kill pests and if misused can contribute to problems. But that’s a far cry from the irresponsible neonic alarm bells set off by the Sierra Club. In fact, studies show that other pesticides, such as pythrethroids and organophosphates, which some ‘environmentalists’ have suggested should be substituted for neonoics (and are now being used in parts of Europe where temporary bans are in place) pose far more significant health hazards to bees–and to humans. According to a recent report in Phys.org–widely respected for its independent science perspective:

Beekeepers’ biggest challenge today is probably Varroa destructor, an aptly named parasitic mite that we call the vampire of the bee world. Varroa feeds on hemolymph (the insect “blood”) of adult and developing honey bees. In the process it transmits pathogens and suppresses bees’ immune response. They are fairly large relative to bees: for perspective, imagine a parasite the size of a dinner plate feeding on you. And individual bees often are hosts to multiple mites.

Beekeepers often must use miticides to control Varroa. Miticides are designed specifically to control mites, but some widely used products have been shown to have negative effects on bees, such as physical abnormalities, atypical behavior and increased mortality rates. Other currently used commercial miticides have lost or are rapidly losing their efficacy because Varroa are developing resistance to them.

While the media and anti-pesticide advocates are often all too delighted to seize on one study or another reporting adverse consequences from neonic use, the clearest picture of overall bee health can be found in the fields and measured by colony numbers and strength, and the actual crop production and agricultural output. In one of the largest field studies to date, a team led by Natural Resources Institute of Finland researcher Jarmo Ketola, in a field study over two growing seasons (2013 and 2014) of turnip rape in Finland, found that field exposure of bees to the neonic thiamethoxam seed-treated crops had no adverse effects on honey bee colonies.

Without bees we’ll lose family farms–not true. Another misleading Sierra Club claim is that the world food supply is endangered by bee losses. Bees are important pollinators, but overall they are responsible for pollinating about 1/7 of the food we eat, not 1/3 (pollination can come from other sources besides honeybees). As the Genetic Literacy Project observed last year:

Sixty percent of America’s crops can grow just fine without bees. Wheat, corn and rice are wind-pollinated. Lettuce, beans and tomatoes are self-pollinated. The 12 crops that worldwide furnish nearly 90 percent of the world’s food — rice, wheat, maize (corn), sorghums, millets, rye, and barley, and potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassavas or maniocs, bananas and coconuts — are wind pollinated, self-pollinated or are propagated asexually or develop without the need for fertilization.

For many crops, bees are absolutely essential for pollination and reproduction. But that’s not true for most of the crops we grow.

Sierra Club solution

It can be summed up in four words: blame Monsanto and give money (and lot’s of it). Monsanto, the bogeyman of anti-chemical activists, manages to make its way into almost every Sierra Club appeal even though the company doesn’t make any insecticides. But Bayer (which is hoping for approval of its proposed purchase of Monsanto) does, so more recent appeals have begun targeting the German corporation. And so do six other companies, including Syngenta, Sumitomo Chemical, Nippon Soda and Mitsui.

Brune also offers those frightened by the impending demise of the world bee population a few specific recommendations:

- Plant the seeds I’ve sent. This mix of bee-friendly flower seeds has not been poisoned by neonicotinoids, so they’ll provide a safe source of food to help support our bee population.

- Sign the enclosed petition to House Minority Leader, Nancy Pelosi, urging her to use all the powers of her office to pass H.R. 1284 — The Saving America’s Pollinators Act of 2015, to suspend the use of bee-killing neonicotinoids immediately!

- Join the Sierra Club with a gift of just $19 or more–an incredible bargain at about a nickel a day–to support our efforts to save the bees, protect the environment, and stand up for beekeepers and small businesses across the nation.

It’s sobering to pragmatic, solution-focused environmentalists to see just how far the Sierra Club’s reputation has plummeted in recent years. Once an organization focused on the conservation of wild areas and national parks (John Muir was instrumental in establishing the National Park and wilderness protection system in the American West), it has changed its mission significantly, and even more so this decade.

Executive director and chairman Carl Pope, who led the organization until 2011, was known (and criticized) for being willing to work with businesses and other organizations not seen as friendly to environmental groups. Pope’s goal was constructive change, not just campaigns.

“I’m a big tent guy,” he told the Los Angeles Times shortly after leaving as head of Sierra Club.

Brune, his successor, had very different ideas upon assuming the helm. He advocated a more “grass roots” approach, reflecting a confrontational style honed at the Rainforest Action Network and Greenpeace. Under his leadership, it abandoned its open-minded view of biotechnology to adapt the shrill style of Greenpeace and other old school anti-technology NGOs.

The campaign against neonics was being conducted by the Club’s Pollinator Protection Campaign, led by Laurel Hopwood, until it was turned over to the Club’s Agriculture Team this fall. Intriguingly, Hopwood’s August letter to volunteers announcing the change discussed the lawsuits and petitions the Club has made in attempts to ban neonics, but also mentioned something of a rift with other environmental groups that are more grounded in empirical science:

This campaign began when (The Sierra Club’s Genetic Engineering Action Team) GEAT learned about the link between the honeybee demise and neonic coated seeds. We contacted other major groups in the U.S. to help with this critical issue, but were turned down. Hence, we ran our own campaign.

If you send your money in now, at least you’ll get a nice Sierra Club tote bag or a 2017 calendar.

Andrew Porterfield is a writer, editor and communications consultant for academic institutions, companies and nonprofits in the life sciences. He is based in Camarillo, California. Follow @AMPorterfield on Twitter.

Jon Entine is executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project. His Twitter handle is @jonentine.com.