Another week, another terrorist attack. As the body counts from terrorist attacks continued to mount, questions of what impels people to plan and carry out these attacks also continued to mount. One area of research is our own biology — could a combination of genes, brain physiology and psychology be behind suicide bombers, machine gun-toting operatives or airline hijackers?

For decades, anti-terrorism research focused on relatively obvious societal issues, but also genes and neurobiology — looking at brain scans for profiles of killers and genes to show that terrorists were different from the rest of us. But what is a terrorist, really? Is he or she different from a murderer or even a serial killer? If gun violence in general has dropped in the past 20 years, as a Pew Research Center report shows, then why are these types of killings on the rise?

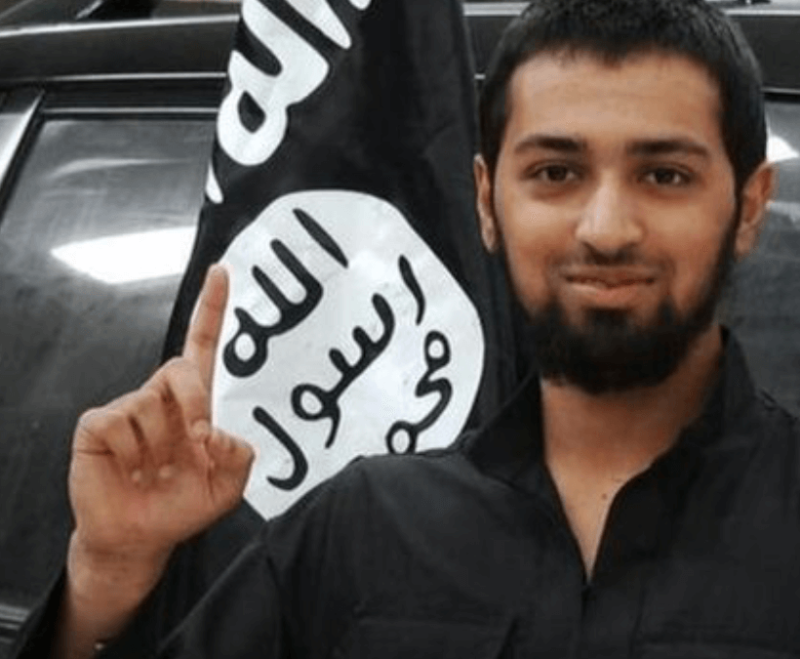

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, much research on terrorism has tried to understand the basis of radicalization — the recruitment and cultivation of people to hold politically extreme beliefs, and carry out acts that are clearly suicidal. Such radical attitudes have been seen as behind many acts of terrorism, including mass shootings, hijackings, kidnappings and suicide bombings. And radicalism hasn’t been limited to groups like Al Qaeda and Islamic State; they may also include left-wing groups like Germany’s Baader Meinhoff Gang/Red Army Faction, which killed 30 people during a campaign against high-profile Germans and US military personnel in the 1960s and 70s, and people following Venezuelan terrorist Illich Ramirez Sanchez (“Carlos the Jackal”), who remains in prison after masterminding the killing of 11 people in the early 1980s.

But even the concept of “radicalism” as a cause of terrorism has some detractors. John Horgan, a terrorism specialist at Penn State University, wrote recently that the concept has forced researchers into fruitless avenues of inquiry:

Rooting out radicalization has become a proxy for pre-empting terrorism. But this logic, compelling as it was, faces some serious obstacles. It appears to be generally accepted wisdom that not everyone who holds radical beliefs will engage in illegal behavior. Though the consequences of terrorist atrocities are far-reaching, they continue to be perpetrated by very few individuals.

Current research shows no smoking gun

So, if it’s not militant, radical beliefs that trigger terrorist murder and mayhem, then are there any biological correlates? Why do young, relatively innocent people agree to sacrifice their lives for terrorist organizations? What motivates them, and how can this motivation be stopped without gunfire? So far, the neuroscience of terrorism has yielded few clues:

- Swedish researchers found two genes, monoamine oxidase (MAOA), and cadherin 13, which when mutated appeared to correlate with violent, even homicidal behavior. MAOA helps control dopamine levels in the brain (thus controlling feelings of well-being or happiness), and cadherin-13 helps control impulsive behavior. But a connection between these naturally occurring regulators and terrorist behavior has yet to be made clear.

- Since the 1970s, security and police in Israel (and since 9/11 in the United States) have used and refined behavioral profiling and “body language” clues to intercept suspected terrorists. Behavioral scientists like Paul Ekman and the Salk Institute’s Terry Sejnowski have been looking for a range of unconscious or conscious behavioral triggers (and their correlates in the nervous system) that could reveal a violent intent. Sejnowski has looked at ways computer programs could detect unusual behaviors.

- fMRI, CAT and other brain scan data have revealed some profiles of violent criminals. But as the UC Irvine neuroscientist Jim Fallon showed with his own scan, not all profiles predict violent behavior. And so far, no profile of a terrorist has been identified.

- Researchers also have looked at the neurobiology of deeply held religious beliefs, under the hypothesis that deep-seated attitudes could produce certain physiological traits that lend themselves more easily to terrorist acts. A group of National Institute of Aging scientists identified a number of brain regions preferentially used by religious research subjects. But not all religious people are terrorists.

The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the “deep science” arm of the US Department of Defense, has been funding research projects (and conducting a few studies of its own), particularly since the 9/11 attacks. At a recent workshop, scientists compared data from fMRI and physiological studies, and warned that the scientific basis of fear, aggression and other behaviors associated with terrorism did not yet add up to a biological definition of terrorism. At the workshop, DARPA’s Lt. Colonel William Casebeer noted that supporting more neuroscience research of terrorism would:

Increase decision-makers’ situational awareness by providing a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying violence of this sort.

Result in the development of better models and simulations.

Help cue intelligence collection (in order to make decisions, the intelligence community needs to have information)

Lead to new and innovative back doors for influence (for example, if oxytocin is as important to trust as the research suggests and having a massage increases endogenous oxytocin production, it would be important to know whether Russian President Vladimir Putin had had a massage before a critical negotiation).

Cultural component

But not all explanations behind terrorism will be biological, experts predict. As the American Psychological Association observed, most terrorists are not pathological in the sense that mass murderers and other violent criminals often are.

And not every terrorist or “mass shooter” fits a given profile. Peter Langman, a psychologist and specialist in mass school shootings told the National Journal:

Some would classify as psychopathic. These shooters lack empathy and are sometimes sadistic. Psychotic shooters, like the Virginia Tech shooter, may have schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. They often have trouble functioning socially and emotionally. Finally, traumatized shooters are those who may have grown up in dysfunctional families and suffered physical, mental, or sexual abuse. Some choose to go on a shooting spree at college, others in middle or high school. Some target specific people they feel have wronged them, while others want to inflict as much harm as possible on random victims. There’s no single profile.

Neuroscience and behavioral science have not yet allowed us to use biology to draw distinctions between a more political terrorist and someone shooting up a school or public building. But terrorist organizations thrive from people who feel angry, alienated, and powerless to make real change, and don’t have a problem with engaging in violent acts against governments. After all, one group’s terrorist is another group’s freedom fighter. And it’s still within the realm of possibility to use our knowledge of the brain to influence these individuals to find other ways to resolve their issues.

Andrew Porterfield is a writer, editor and communications consultant for academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. He is based in Camarillo, California. Follow @AMPorterfield on Twitter.